For clients who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, the key to achieving and maintaining health is stable, safe housing. And yet, in so many cases, the only place where the housing and healthcare systems intersect is in the homeless client's experience.

NMCHIR Intersection of Health and Homelessness System Study

Stakeholders:

Michigan DHHS; county health departments; homelessness prevention workers; physical and behavioral health practitioners; homeless, at-risk and formerly homeless individuals; homelessness non-profit leaders and case workers

Human-Centered Design Services:

Research, Facilitate,

Map, Communicate, Conceptualize, Prototype, Implement

We know that the individuals we encounter in a healthcare setting have a variety of challenges that impact their lives, and that the role of healthcare providers is to help them manage those challenges. Homelessness is one of the top-ranked social determinants of health identified by the NMCHIR as a “barrier to health and quality of life.”

We’ve been engaged in a process to better understand the needs of our homeless populations, the constraints and confusion that healthcare workers have shared about addressing homelessness, and how best to connect the healthcare and homelessness systems to keep people from falling through the cracks.

This summary video tells the story of our 2019 progress; we completed the grant cycle in September 2020 and helped the CHIR build out a web repository with all of our findings, resources and recommendations: The Intersection of Health and Homelessness.

“The team at Connect_CX are stellar systems thinkers.”

— Emily Llore, NMCHIR Director of Community Health Assessment and Improvement Planning

A video summary of the process and outcomes of the NMCHIR Homeless Response System project, aimed at creating connections between complex systems to better support our neighbors at risk.

Research & Facilitate

Key to our discovery process was convening practitioners from both systems in a series of collegial, proactive conversations that led us to preliminary conclusions about how the system works (or doesn’t) and the resources and constraints that each have to offer. We worked closely together to co-design solutions related to policy, data sharing, training opportunities, shared language and more effective use of existing resources. We began the process by hearing directly from people on all sides: in-person and online interviews that humanize the challenges each person faces.

7 literally homeless and 3 formerly homeless individuals;

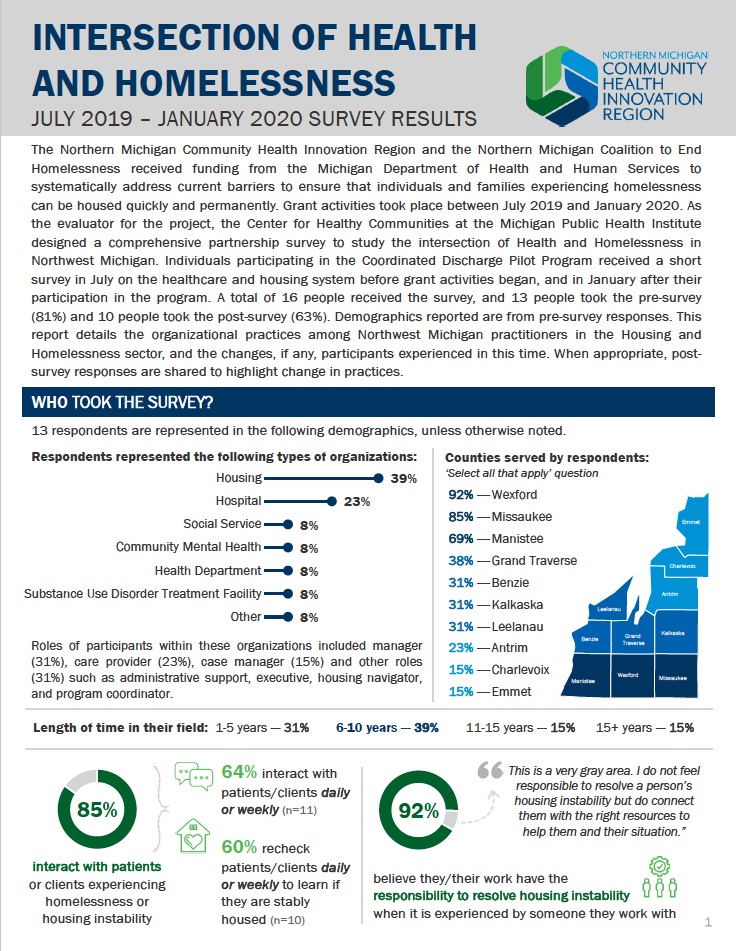

8 healthcare leaders and managers; and, via online survey

102 healthcare, homeless response and social service practitioners throughout the 10-county region.

From these interviews, we heard the following:

“I guess I’m just not crazy enough for Community Mental Health.”

“(The ER staff) treat you like crap … and they don’t care. I’d rather die than go back in there.”

“I always have the same doctor … I’ve learned how to manage my conditions, eating habits, medications … it’s been very good”

“I needed to see a neurologist in Ann Arbor. The cost of the visit was covered, but there was nothing for transportation. NMSH (a local nonprofit) was able to find the money.”

Of the almost 1000 people that have experienced homelessness in our region:

66% had one or more physical or behavioral health conditions

77% had a valid form of health insurance, most often employer-provided

For healthcare providers, more than 70% reported daily or weekly interactions with clients not stably housed; of these, Less than 50% report personal confidence in helping these clients, and less than 35% rate their organization as effective in meeting the needs of homeless clients.

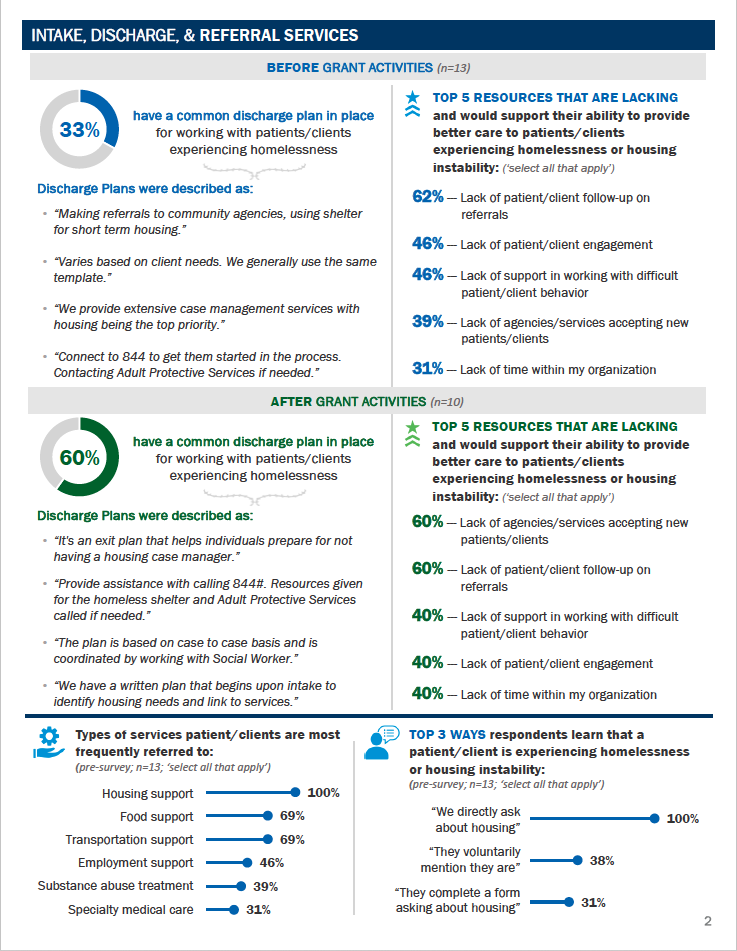

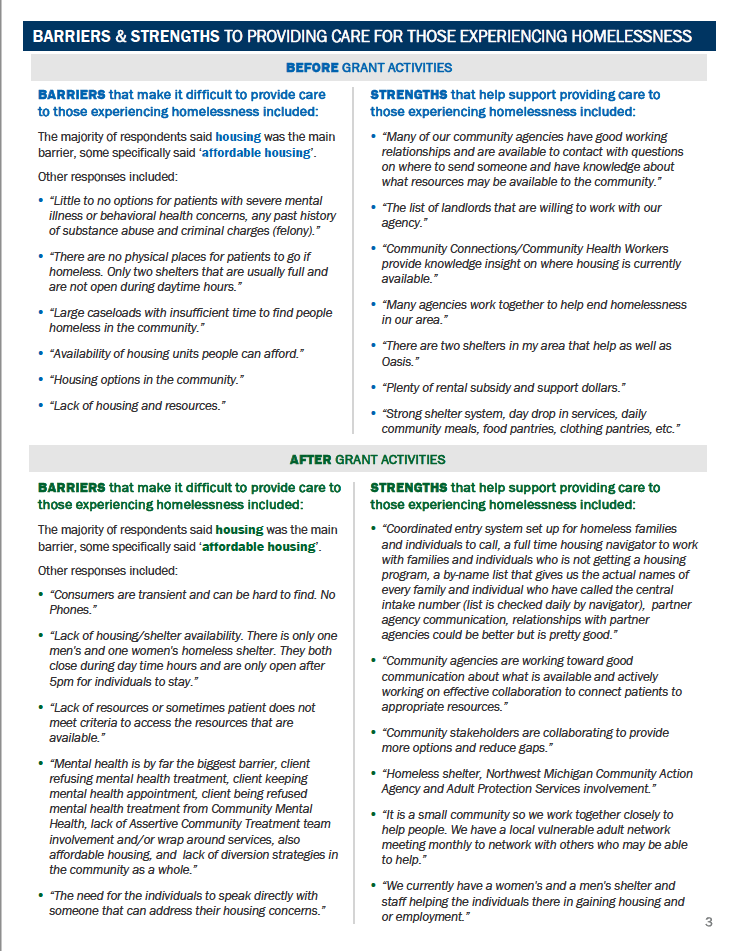

The problem we’ve seen is that few patients self-identify as homeless, and often don’t “look homeless” when they present with health problems. Healthcare providers have no consistent approach to finding out whether their patients are homeless and, even if that discovery is made, very few resources to help them once they’re released:

Limited capacity in shelters, if they exist at all;

25-30 available housing program slots per year; and

Difficulty in finding affordable housing for those who qualify for help.

For this reason and many others, the average length of time an individual spends homeless in our 10-county region had increased from 119 to 153 days in 2018.

Map, Communicate, Conceptualize

So how do these systems actually work? And what means can we use to develop a shared understanding of the landscape that clients experience as they navigate? We explored system disconnects with providers in Substance Use Disorder and Healthcare emergency, inpatient and outpatient settings.

We listened to their stories, and traced the path of each client as they moved from system to system.

We then translated their stories using a service design model, outlining each phase of the pathway, and the decisions faced by providers represented; then

We developed a metaphor called the “Belt & Pulley” to illustrate this idea. Each pulley represents a system, with defined boundaries and functionality; the belt represents a given pathway that a client follows as they move between systems.

We believe that five things are true of this metaphor:

The systems represented work in similar ways, but are disconnected

Homelessness, a major predictor of health and behavioral issues, drives the system as we’ve defined it

The extent to which behavioral issues come into play increases stress on the system as its experienced both by the client, and providers on each side.

At any given time, clients can be caught in sub-loops, which may ultimately lead to transitions to other systems, and

The clients we’re addressing in this project, those at risk of homelessness, rarely leave the system completely.

Prototype & Test

We translated all of the feedback into a series of digital decision trees we’ve developed for health and homeless service providers, law enforcement and other community members who can proactively identify and respond to someone at risk of homelessness. Working closely with them, we’ve learned what’s both appropriate and needed in these contexts.

These can be printed at low cost and posted in workstations, added to existing Electronic Health Records software platforms or be located on healthcare providers’ Intranet sites.

Communicate

To illustrate all of this, we’ve told Catherine’s Story (not her real name) in a separate video.

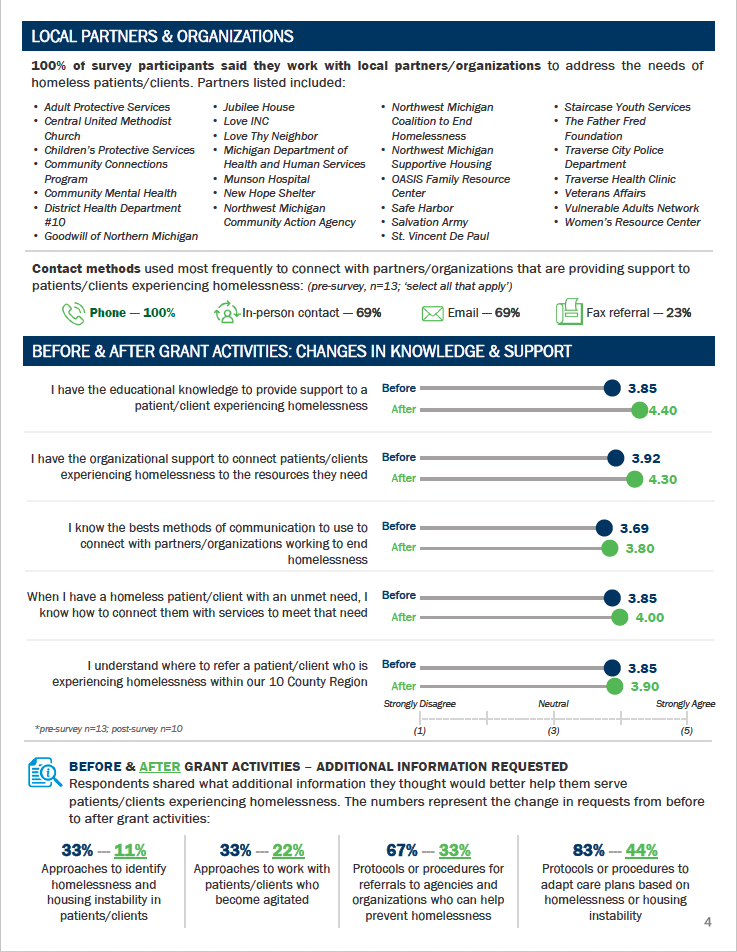

Through the process, we’ve worked to develop shared language, enhanced communication strategies, more effective use of existing resources, policy changes, a toolkit for replicating the process and cross training opportunities for providers throughout our region.

Here’s just one example of how we’ve applied our human-centered approach: we’ve learned from clients that the language we use (housing case manager, diversion planner, navigator, substance use counselor) isn’t necessarily what they understand. So rather than use these terms, we’re now asking who their “worker” is.

Implement

Experts in homelessness prevention have been involved at each point in our process, and have responded by engaging healthcare providers in:

Policy recommendations for both healthcare and homeless response providers such as consistently asking housing status questions upon intake, throughout treatment and prior to discharge;

Proactively addressing releases of information (ROI) to smooth out handoffs between systems

Diversion training, helping clients find alternatives to shelter and keep them out of the system altogether, and if that doesn’t work,

Connecting clients to homeless response via a toll-free 844 number, and helping them navigate the transition between systems.

We’ve found that, even though the systems are complex, by taking a relatively small number of defined, somewhat complicated actions, we can work together to improve experiences for those at risk of homelessness.

Research Summary

Throughout 2019, we worked closely with the the statewide CHIR through the Michigan Public Health Institute. They helped us design, build and launch the survey in our 10-county region, then aggregated the results with other CHIR areas undertaking similar efforts. This helped the Michigan DHHS and the statewide director of the CHIR see how each region was working, and which efforts were most effective. Complete results of our 2019 collaboration are available if you simply connect with us via our email form.

Thank you for your interest, and your contributions to this important work.